By Sharon Thompson

One year ago today, Aug. 4, 2014, a tailings dam failed at the Mount Polley mine in British Columbia, sending 6.6 billion gallons of toxins downriver, tainting waters flowing into the Fraser River, one of Canada's most prolific salmon producers. Though the economic, social, and environmental costs of the disaster will not be fully known for a long time, the event hit extremely close to home for my family and neighbors. We felt for those living in the impact zone, and saw our concerns about developing the Pebble deposit come to life.

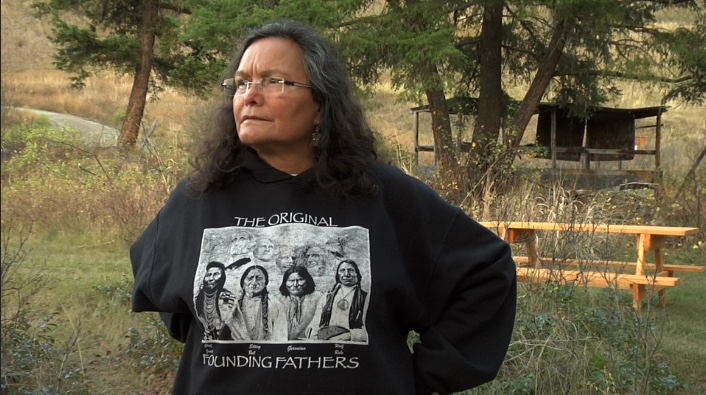

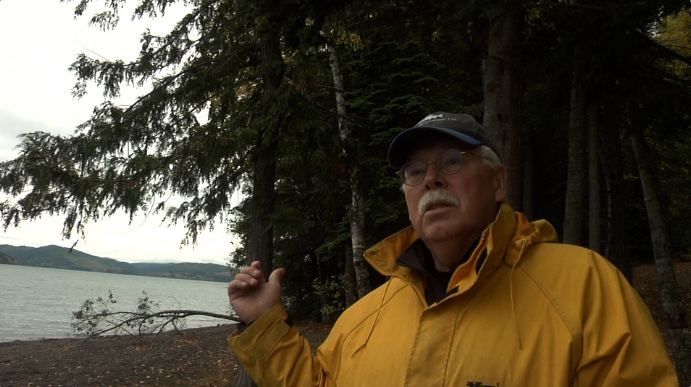

Living in Bristol Bay, downstream from the proposed Pebble Mine, the tailings dam failure at Mount Polley represented our worst nightmare, something we have feared for nearly a decade as the fight against Pebble Mine continues within the region. Wanting to better understand the impacts of the spill, some members of the local tribal coalition, Nunamta Aulukestai, took a trip to see the damage firsthand. I went with them and met with Chief Bev Sellars of the Xatśūll First Nation in British Columbia. She and her daughter, Jacinda Mack, gave us a guided tour of the impact zone and a glimpse into how this disaster has altered the lives of tribal members and other residents.

Chief Sellars said the members of the community came together for a meeting right after they'd heard the news and viewed initial pictures of the breach. "The heartache and the tears and the worry and the fear in our members was just so heartbreaking," she said.

"It was like we lost a whole village," Jacinda said. "In the area where all the tailings came down the mountain, on Hazeltine Creek, there were four villages there before. And the feeling is we lost those villages twice. We lost them to smallpox. Now we have lost them to this. It's a devastation on top of a devastation."

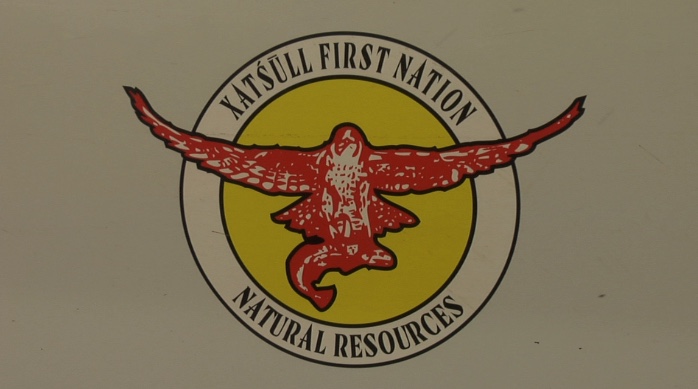

They took us on a skiff ride across Quesnel Lake, which used to be crystal clear but now has a cloudy plume of contaminants moving through it. Jacinda pointed out all the houses. "None of these people have clean water now," she said. "People out here are talking about the impacts this has had on them: nightmares, worries of another event coming down, not being able to water their gardens that they worked on all summer for food, having to buy water, the drinking water ban lifted and then re-instated. There's just so much confusion, anger, frustration, and so many unknowns."

At the mouth of Hazeltine Creek, we watched a crew working to clean up floating trees and debris from the area. Chief Sellars described this creek, formerly a few meters wide, as small and productive, with lots of Coho and other fish. Now, after the force of 10 billion liters of water and 4.5 million cubic meters of toxic silt gushed down from the tailings facility, Hazeltine Creek has expanded to 200 feet in some places and to about 400 feet wide at the mouth.

"We went on a tour of the mine site further up, and areas that I'd been to, oh my god, a hundred times. I didn't even recognize it. It was like a foreign landscape," Sellars said. "It looked like, well, a bomb did go off there. I couldn't believe it." We could see grey sludge upstream covering just about everything where the big village used to be. Even then, residents were still cleaning up the area and couldn't drink water from the tap.

It was clear that losing the ability to fish here is a huge loss for them personally, as well as for the community and culture. Chief Sellars and Jacinda walked us through their heritage village on the banks of the Fraser River and retold memories of salmon season, visiting with neighbors, and putting up fish, calling it a 'magical time.' But those days are now in the past. "A lot of our community members haven't got their fish for the year, because they were scared to catch any fish. So a lot of their freezers are empty. You know, fish that they need to survive the winter," Jacinda said.

I felt guilty at this point — our freezers were full. Bristol Bay had another amazing return of salmon last summer and this one as well. My husband fishes commercially, our main source of income for the year. The kids and I put out our subsistence net and brought fish to my sister's to fillet, vacuum-pack and smoke. Our extended family and neighbors all do the same. My baby girl is now cutting her teeth on smoked fish strips. We are fortunate that the water from our well is pure.

For years we have worried that our spawning grounds will be contaminated by pollution from the proposed Pebble Mine. After years of being ignored by our state government, last summer our federal government responded to the concerns of people here and moved forward with proposed protections for our salmon through the Clean Water Act. Then over the winter, the Pebble Partnership stepped in, again completely ignoring the overwhelming desires of nearby communities, by filing lawsuits to delay these protections. So far these delay tactics are working. I can't believe that it's 2015 and Pebble is still a very real threat.

Not long ago, the news broke that B.C. issued Imperial Metals, the owners of the Mount Polley mine, a conditional operating permit to begin discharging at the site once again, despite the fact that none of the recommended safety improvements made by a panel of independent reviewers had been completed. This news was disappointing, but not surprising. Imperial Metals and Pebble Limited Partnership have a few things in common, one being the designer of the tailings dam that failed, Knight Piesold, the same firm that Pebble Partnership hired to design their proposed tailings dams.

"This [Mt. Polley] mine that has been hailed all over the world as one of the best mining examples has created one of the worst environmental disasters in Canada," Jacinda said. "This is our territory, this is our homeland and now, this is our inheritance. This is what we have to pass on to our kids. We'll be dealing with this for the rest of our lives. And so will they."

Sadly, their tragedy is our wake up call. Hopefully we can prevent the same devastation and have a thriving fishery to pass on to our children. We asked Chief Sellars what we could do to help. She looked at me and said, "Stop Pebble Mine."

Sharon Thompson lives in Naknek, Alaska.